Glacier Bay Glimmers

by John Burbidge

We had to get off the water. A capsize in the icy, stormy waters of Glacier Bay is a life or death situation, and we absolutely could not risk it. And what about that tiny creature who had tagged along with us on this wilderness adventure? Could he or she even survive a shock like that? Maybe. Maybe not. We had to get off the water.

The waves crashed against the cliff beside us and surged back, swirling in different directions. The wind swooping in from behind created large, forceful swells that “surfed” us down their faces faster than we wanted to go. If a wave rolled one of us we would be upside down in the freezing water, desperately trying to get out of the tight cockpit and back to the surface where the real challenge awaited—re-entering a swamped kayak during an Alaskan windstorm, body-clock ticking toward hypothermia. Good luck.

I yelled to Claire that we should aim for a small point of land about a mile ahead. She nodded but kept her eyes on the water, bracing to stay upright, making slow but steady progress. Antsy and ready to bust out full speed, I kept looking back, searching for signs of panic. All I saw was wide-eyed determination, maternal instincts in overdrive. Claire understood the stakes. I knew she would give everything she had.

Surf, brace, paddle. Surf, brace, paddle. Finally, 30 minutes later, we pulled around the point and slid into calm water. We breathed a sigh of relief and floated limply, got our wits back. Eventually we consulted the map and surveyed the shoreline, where a river snaked through some grassy fields and flowed into the bay. The map indicated this area was closed to landing and camping. Why? An unusually high concentration of bears.

Great. We eyed the shoreline nervously. Bears in here, big waves out there. What the hell do we do now?

Critical stages

I believe our baby was conceived the day Claire and I went sea kayaking in Puget Sound and got surrounded by porpoises. They danced beside us for 15 minutes as we floated a mile offshore on the west side of Whidbey Island, our home. They smiled as if they knew something we didn’t.

They did. We found out a few weeks later—less than a month before we were to embark on our biggest sea kayaking adventure yet, a two-week, unguided, no-group, just-us journey through Glacier Bay National Park in Alaska. Now this.

I wasn’t sure what to think. Oh of course I’m happy, I’m ecstatic, we’ve been blessed. But can we still go on our trip?

Some family and friends expressed concern and urged us to cancel. Critical stages, one friend kept telling me, the early weeks are critical stages. Why take the chance? You’ve got more important responsibilities now.

Claire asked her doctor. The doctor was oddly casual about it, said sure, go ahead. I was glad to hear this, but also insulted. I wondered if that doctor knew anything about the Alaskan wilderness. We’d be paddling 20 miles a day through icy waters, carrying heavy boats and bags of gear up long, rocky beaches. This trip would be harder than that doctor thought.

But the doctor’s blessing tipped the scales for Claire. She knew how much this trip meant to me—this was the end of my life as I knew it. Thirty-eight years old and the door to personal freedom was finally going to shut me out. No more adventures, at least not for a long time. Chained to a freaking stroller.

Did I pressure her into sticking with our plans? Not overtly. I played the role of concerned dad-to-be, threw in plenty of “whatever you think is best” statements. And if she’d said no, I’d have abided without a big fuss.

But she didn’t say no. Claire likes adventures too, that’s why we got married, right? She wanted to go. She was comfortable with her doctor; she trusted me to plan a safe trip. I’d planned many safe trips for us in the past.

And I did plan a safe trip. In Alaska, though, “safe” revealed itself to be the entirely relative concept that it is.

The tame part of the trip

So it was I found myself in the middle of the night on the MV Columbia, duct- taping our tent to the ship’s deck in a pounding windstorm. Claire was inside lying spread-eagle on the floor, a human anchor.

Christ, I thought, tying a guy-line to a handrail with a series of desperate, sloppy knots, rain whipping at my face—is my tent even going to survive the ferry ride? We’re only a few hours up the Inside Passage and I feel like I’m fighting for my life.

Out of the dark a guy from Australia appeared; he was camped two tents over. I’d talked to him and his wife briefly earlier that day. They were on their way to Skagway to backpack the world famous Chilkoot Pass trail, the same route Jack London and the gold miners followed. We teamed up to secure the tents, then dove back inside.

The next day the four of us moved camp down one level to a more sheltered location. It was near the engines—rumbly, a little fumy—but at least we weren’t worried about being blown overboard into the frigid waters of the Inside Passage and sinking, trapped inside our tents, never to be seen again.

Video

Click below to watch a YouTube video of amazing wildlife and scenery in Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska.

You get what you pay for

If taping a tent to the wet deck of a boat doesn't sound like your idea of a luxury cruise, you’re starting to get a clue about traveling on the Alaska Marine Highway. Sure, you can rent a cabin if you reserve it a year in advance. The cabins are basic, but they are warm and out of the wind and not prohibitively expensive.

Despite this, many people, including families with small kids, choose to camp on the deck free of charge. Others sleep in the Solarium, a heated area on the top deck with a ceiling and three walls. Then there are others who just wander around, crashing in places they’re not supposed to like the TV lounge, but only getting minimally harassed by the workers. The crew goes out of their way to make sure nobody feels like a second-class citizen.

Many of the deck-campers are obviously hardened seasonal workers or Alaskans on their way home from visiting the Lower 48. Claire and I observed their travel habits and quickly got a system down, and for the rest of the three-day journey to Juneau, we simply strolled around the boat watching for whales, or sat in the large observation lounge, listening to the lectures provided by the on-board Forest Service naturalist.

Aside from that first night, the boat ride proved to be a relaxing exploration of a corner of the planet I’d always dreamed of seeing, the famous Inside Passage. A shimmering, protected waterway lined with dense forests and snow-topped mountains, the Passage stretches 900 miles from Vancouver Island to Cross Sound, though for many the real terminus is Skagway at the head of Taiya Inlet. Yes, cruise ships ply the Inside Passage regularly. Ignore them. Take the ferry. Come see this place before you die.

Bird’s eye view

Juneau shook us out of our reverie. We departed the ship to catch a small plane 40 miles over to Gustavus, a town about 10 miles from Bartlett Cove, the headquarters of Glacier Bay National Park and our launch point.

Like most places in Southeast Alaska, there is no road access to Gustavus. A private ferry sails six days a week ($100/pp one way), or a plane can be chartered any day, weather permitting ($60/pp one way). We chose the plane to save time and get a different perspective on the Alaskan wilderness.

As we rose over the mountains and water, I asked our pilot Chuck what he thought of Glacier Bay. “It’s nice,” he said, “though it can be a bit wet over there.” Of course I knew that already, but his understated manner made me wonder.

Chuck refocused my attention when he pointed at some humpback whales surfacing below in a glassy bay. He dipped the plane down for a close-up of the giant sea creatures, then zoomed back up. Just another day at the office.

Crammed into the plane with us were a man and woman from New England. Because we were sitting on our bags of gear, it was impossible not to compare who had more. We had more—a lot more. Not only that, but we had two big boxes of food waiting for us at the post office in Gustavus, whereas the other couple had all their food with them. The question went unasked: Were we overpacked or were they underpacked?

Six days later we would cross paths in Muir Inlet, and the answer would be obvious.

Anomaly, anyone?

In Gustavus we were picked up at the airport by Ed Bond who runs Sea Otter Kayaks. He rents boats and guides trips. Ed eyed Claire and I suspiciously, wondering if we were up to the challenge of an unguided 12-day trip. “Do you guys have fleece?” he asked, motioning at our jeans and flannel shirts. Yes, Ed, we have fleece. Soon Ed was focusing on the New England couple. They had a lot more questions.

Ed shuttled us over to the Glacier Bay Lodge at Bartlett Cove. Its upscale presence was jarring after our long journey. Had we come so far from civilization only to be thrust right back into it—in sickening luxury?

We pondered that quandary as we savored a fancy meal in the lodge’s restaurant, then lounged around the fireplace in the main room. “I suppose I could get used to this,” I said, sipping a microbrew. Claire nodded and wiggled her toes at the crackling flames.

But we were posers, and finally we had to trudge a half-mile back down the trail to the free campground. We wormed into our tent and fell asleep to the tapping rain, thinking about tomorrow. Tomorrow . . . that's when the read deal began.

Trip Log: Day One

Paddle in the rain.

Trip Log: Day Two

Paddle in the rain.

Trip Log: Day Three

Paddle in the rain.

Trip Log: Day Four

Paddle in the rain.

Trip Log: Day Five

Paddle in the rain.

Okay, so there was more to it than that. But I want to make a point here. After five consecutive days of paddling in the rain, your mind starts playing tricks on you. It starts tricking you into thinking you are cold, wet, and miserable. Wait, it’s not a trick—you are cold, wet, and miserable.

Well, maybe not entirely miserable. Despite the weather, Glacier Bay had started to reveal its wild magic to us. About 30 minutes after we launched we saw a black bear walking on a beach. Hmmm, I thought, remembering the mandatory, 90-minute bear-safety lecture we’d been given by the park rangers. At a rate of one bear every 30 minutes, we’re going to see a lot of bears.

As it turned out we would see five: three blacks and two browns (aka grizzlies). It’s not so much the bears you see in Glacier Bay, it’s bears you don’t see. It’s the psychological effect of all the tracks and scat you observe everywhere you land, or anywhere you want to camp. You come to believe that even if a bear isn't standing in front of you, one is undoubtedly close by, perhaps even watching you. Wondering in its big hairy head what to do about you.

For sure, seeing a bear so soon that first day woke us up to reality. We’d dressed lightly and were already getting cold in the rain, so we pulled over on a beach and put on warmer clothes. Time to get serious. We weren't in Kansas anymore.

Five days of rain to start the trip

Sharing campsites

Despite the rain, the first night was incredible. We camped on a beautiful point of land in the Beardslee Islands, looking out over the vast expanse of Glacier Bay, the grand scale of which no map can adequately convey. Far out on the water, humpback whales spouted and flashed their giant tails; a pod of orcas swam past, impressive black fins knifing in and out of the water. A bull moose fed in the swamp a few hundred yards behind our tent. Wow. Animal Planet. The effect was startling yet sublime.

In the middle of the night I got up to relieve myself. Outside, I heard a deep snort and heavy breathing coming from some tall weeds about 50 yards away. Something big was catching a few zzzz’s in there, probably that moose. Well, he’d get no argument from me. A 1,200-pound moose sleeps anywhere he wants.

But the rain returned on the second day, and on the third day the wind picked up. Two hours after launching we found ourselves fighting desperately for balance in sizable waves along a rocky cliff that offered minimal landing options. That’s when we pulled into the cove that was closed to camping due to a high concentration of bears.

The bear show

We floated in the cove, scanned the map again, confirmed our position. High concentration? Man, we already saw bear tracks and scat everywhere we stopped—how much higher could the “concentration” get? Unfortunately, we had no choice. We could not go back out paddling in those conditions.

The plains where the river flowed into the cove were flat and soft, but we picked a sloping, rocky ledge among some cliffs near the edge of the cove. We gladly traded physical comfort for psychological relief. The only way a bear could get us here would be to rappel in from above.

We relaxed and cooked our dinner. Thousands of birds swooped around the cove, diving, feeding, squawking. For the first time in three days, the rain let us eat in peace. Everything had worked out after all.

Before bed I made a closer examination of the cliff behind us. Maddeningly, I discovered a giant bear poop at the base of the one single weakness in the cliff, a ridiculously steep gully. The poop was old, but it was there. I looked up the dark, wet, tree-choked gully, thinking you have got to be kidding me. A bear came down that?

The next morning dawned calm. The rain splashed on the brims of our hats as we slipped our boats into the smooth water and began paddling. An hour later, a humpback surfaced right in front of us. Claire saw it, but I missed it.

I stayed annoyed with myself until I spotted a black bear on a beach, just before we stopped for lunch. I pulled my boat close and watched the bear lick mussels. He looked at me, then looked away. He had shells to lick.

The bears put on a much better performance that evening. Claire and I were lounging resolutely in the rain on the beach at Muir Point, watching wildlife through binoculars. Four straight days of rain, we still managed to be chipper. We talked about John Muir, who built a cabin on this site 100 years ago to study the glaciers, which at that time extended all the way here. John Muir, man, that guy had guts. Imagine all the—

Our hearts kicked up a notch as a black bear stepped out of the bushes about 200 yards away and started scrounging for food. We took turns with the binoculars and debated whether he was headed our way. We forgot about John Whatsisname.

Suddenly another bear—huge, brown, with massive humped shoulders—sprang out of the bushes near the edge of the beach and charged the first bear. Like a launched rocket the first bear leaped into the air and soared into the bushes. In hot pursuit, the giant brown bear went crashing in behind. Then they were gone.

We stood there stunned. Holy crap, did you see that big brown bear move? The King of the Beach. And not afraid to prove it.

The looming nightfall took on heavier meaning. We pitched our tent against a protective bank of dirt and then arranged our kayaks into a barricade on the other side. We knew our little fort was an insane, useless undertaking. We made it anyway.

It can be kind of wet over there

On the fifth straight day of rain, we saw the New England couple headed out. We pulled our boats close to chat. The woman wore a small wool hat; the man wore a cotton baseball cap. They eyed our full-brimmed Gor-tex rain hats like starving lions eyeing chunks of meat in a trainer’s hand.

They talked of being cold and wet and seemed ready to get out of Glacier Bay; tomorrow a powerboat would pick them up and take them back to the lodge. When we told them we still had another seven days, they called us hardcore, then paddled off.

We shook our heads at “hardcore.” The rain was getting to us, too. I don’t care what equipment you have, after five days of rain your clothes are wet, your tent is wet, and your sleeping bag is clammy. It all still works, but it’s wet. And you’re sick of it.

It came to a head that evening as the rain poured steadily on us throughout dinner. Stupidly, I’d used our dinner tarp to cushion the tent because the only spot available was a bed of sharp stones. So we sat on mussel-ridden, wet rocks in the intertidal zone, spooning freeze-dried food into our mouths, rain streaming off the brims of our rain hats onto our laps. It was a meal of complete and utter wretchedness.

For the first time, Claire complained bitterly. She was hungry all the time, chilled and weak. I understood the subtext: Did that mean the baby was hungry all the time, chilled, and weak? Eat more, I suggested. We don’t have more, she shot back. We left all our extra food in the shed in the campground. Remember?

Of course I remembered. We’d packed hurriedly in the rain that first morning, and although we crammed as much food as we could into the four bearproof cylinders provided by the Park Service, we ran out of room to take much extra. Sure, I could have walked a mile in the rain to get another one, but then we would have missed the tidal current required to get through the narrows behind Lester Island. No, better to take my pregnant wife into the wilderness and starve her to death than miss the favorable tide.

We finished eating in silence, then went to bed. In the middle of the night I performed my ritual of checking outside the tent to make sure the high tide wasn’t going to flood us—every night it rose an incredible 18 vertical feet from its low point. The water’s edge, which had been 100 feet away a few hours earlier, now lapped just a few inches from our door.

But it was starting to recede, so we were okay. Or were we? I looked up at the gray-black sky as heavy drops glanced off my face. More rain tomorrow. I got back in my damp bag and lay sleepless, thinking about the baby, gut churning. How risky is this, after all? Are we still in control here? Sure we are, of course we are.

Aren’t we?

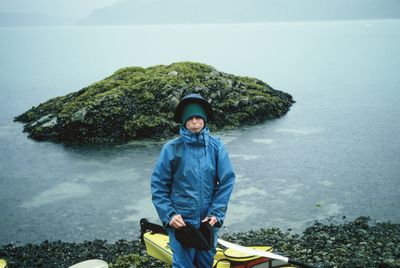

Cold, wet, miserable...and pregnant in Glacier Bay.

The Main Attraction

Unbelievably, the next day dawned clear. The sun emerged over the mountains and soaked us with warmth. We spread our gear on the rocks to dry and lingered giddily over breakfast. The sun, remember the sun? This is awesome!

And today was a big day—glaciers. Finally, after six days, we would encounter the reason everybody supposedly comes to Glacier Bay in the first place. Yesterday we’d seen the first signs; body-size chunks of ice bobbing solemnly down Muir Inlet with the ebbing

tide, broken refugees from the battle raging upstream where giant ice meets giant sea. The glaciers. The booming, crashing glaciers.

So what can I say? The glaciers were awesome, but they were the one part of Glacier Bay I’d experienced through photographs and television shows many times. It was like watching a rerun—a great rerun—whereas everything else was new. We spent a day checking out McBride, watching ice calve into the sea. We ooohed and ahhhed, but the fact is we were probably more interested in the newborn seal pups resting on the ice islands in the lagoon below McBride Glacier.

After McBride, we paddled three miles farther to Riggs Glacier, where we planned to camp and explore. Bear tracks stopped us on the beach—fresh, perfect prints in the tidal mud. Too fresh. We were tired, but we decided to paddle a few more miles. As if we could find a nearby land with no bears. We laughed at ourselves. Right. As if such a thing existed in Glacier Bay.

Sometimes, though, dreams do come true.

The land before life

Imagine a world of jumbled rock and brown dirt, revealed inch by inch from underneath a receding mass of ice. The land is devoid of vegetation, purely empty, and waiting for what the earth will bring: grasses, trees, bugs, animals. On this land an ecosystem will construct itself.

But only in time. As we traveled up the final stretches of Muir Inlet, the hillsides got younger and younger. Where thick blankets of fern would grow, now only scrubby grass had taken root. Where trees would one day tower, now stood only stunted bushes. We’d launched from an old-growth forest at Bartlett Cove a week ago; now we’d arrived at a spot where land itself is born: Muir Glacier at the northern tip of Glacier Bay.

Our spirits were reborn too. For three days in upper Muir Inlet we didn’t see a soul. The sun cooked us back to life, with temps in the 90s as we lounged on rocks and beaches. I could see the tension drain from Claire’s shoulders; if the baby inside her had been weakened by the cold, wet weather and extreme exertion of kayaking through a wilderness, now it could regain strength too. The nagging nervousness in the back of our minds withdrew.

The bears gave us a break, too. Search as we might in upper Muir, we could not find any bear sign near our camps. Gulls nested on the bare hillsides around us, their eggs right on the ground; if any predators were around, those gulls would be nesting on a rocky islet out in the water, as they do throughout the rest of Glacier Bay.

A safe place for babies, for us; a place the bears had not yet arrived. We slept soundly in the upper reaches of Muir Inlet, finally. We began to believe everything was going to be all right, that coming here had not been a fatal mistake after all.

The doctor’s report

That wasn’t the end of our trip. Over the next four days, the wind and rain returned; one day I, the non-pregnant one, got so cold and shaky that we pulled over and finally ate our one extra dinner (seasoned with irony). But the sun was in and out too, and the animals: We saw

wolf tracks at one camp, orcas just off shore in another, and a giant brown bear lumbering along the beach at another. We didn’t have as many miles to make

each day, so physically the trip eased off considerably.

Our last night was clear, calm and warm. After dinner we paddled far out into the center of the main bay and floated, trying to soak it all in before we met the pick-up boat tomorrow and got transported back to the lodge. Mount Fairweather towered 15,320 feet above the water to the west. Porpoises appeared, splashed around us, then swam away; maybe they were delivering a happy message from their friends down in Puget Sound. It seemed like everything had worked out okay, but we wouldn’t know for sure until the post-trip checkup.

Back at the lodge, we splurged for a room. Hot showers, a soft bed, the things we take for granted. Claire ate ravenously that day and every day for the next two weeks as we toured leisurely around Southeast Alaska, doing easy tourist things. We didn’t talk about it, but we were both anxious to get home and see the doctor.

Finally the day arrived. I sat in the waiting room until Claire came out. I looked up to gauge her face and was met with a smile; still, I detected a quizzical edge. The ultrasound revealed the baby was fine, she said. But even with all she’d eaten the past two weeks, she still weighed five pounds less than she did a month ago, before the trip. She’d asked the doctor if that could cause problems, but the doctor told her the baby would simply take what it needed from her, and leave her with less. I know Claire was hungry in Glacier Bay. I suspect I’ll never really know how hungry.

Seven months later, Catherine was born big at 8 pounds 13 ounces. Now she’s 17 months old and we take her for beach walks almost every day on the west side of Whidbey Island. She stares at the breaking waves, giggling to herself, and I wonder if she remembers that sound from Glacier Bay. I wonder if those two weeks on the water will help determine who she is, who she turns out to be. I think I know the answer some days when she grabs her pink sun hat and stands by the front door, issuing her favorite one-word command: “Outside!”

Finally, on the sixth day, the rain stopped and the sun came out!

Copyright © 2022 John Burbidge - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder